Four Elements of Storytelling

Great storytellers dance through stories effortlessly. They know just what to say and when. They compel their audiences to lean closer, pay attention, and remember.

Some storytelling skills may come naturally, or they may develop from upbringing—years of summer camp stories, family barbecues, or long car rides. I also think they can be acquired through conscious awareness, practice, and exposure.

I think there are four interrelated elements to consider when telling any off-the-cuff story: audience, situation, timing, and detail. As a note, I'm going to concentrate mainly on impromptu storytelling, but these elements could easily apply to marketing, movies, fiction, poetry, photography or animation.* Essentially, if you have something to say, then these considerations may help you say it.

Audience

By far, the most important consideration in storytelling is your audience. This might already be apparent to you, and you may already have a strong sense in adapting to an audience. If that's the case, congratulations, you're starting with a huge advantage.

If you don’t have the ability to read an audience, do not despair! All is not lost. You just have to use what you know. Or what you can gather on the spot.

If you’re at a party with old friends, for example, you probably have a deep understanding of the people in the room. You know histories, he-said's, she-said's, secrets, and lies. You know that person went to that school and works there. You know those people live in a house in that town. You know that person's dog bites. You know you're not supposed to talk about that time.

Because you know the undercurrents, you can navigate the waters.

In cases where you have little idea of the audience, you can use context clues to start. Do your best silent Sherlock impression. See a pair of shoes, a nice watch, a couple holding hands, or a person typing away on a cell phone. Eavesdrop on an introduction, or pour someone a glass of wine. Don't worry about deducing everything. Just get a sense. You don't need to draw a picture perfect representation, but rather a stick figure sketch. In pencil.

Those things will give you a great place to start. Now come up with a question or two to break the ice. Compliment the pair of shoes. Ask about the watch. See how long the couple has been together. Ignore the phone typist. Notice and ask questions, so you can add details and shading to your sketch.

People like to be noticed, and they love to talk about themselves. So learn about them, and be genuine about it. If you’re interested, they’ll be interested, and the interaction will become a sharing game. You can let them set the tone for interaction, or you can push and pull your way to better understanding of who they are.

Why is this important? Because without knowing who the audience is, you’ll have no idea how to relate to them. When telling any story, you want to connect and convey. Every story will be received much better if the storyteller and the audience are connected in some way. Storytelling is a symbiotic relationship: the storyteller gets recognition, and the audience receives entertainment.

Situation

For the next element of storytelling, let's move on to situation, which we could also label "context." Regardless if the audience is consistent, the situation will dictate the way a story is told. For example, meeting your girlfriend’s parents for the first time is a much different situation than meeting them for a beer a few years down the road.

It helps to think of situation like a physical space. Imagine a room, with furniture, and lighting, and pictures hanging on the walls. We adjust to physical space in specific ways. We whisper in museums, we duck our heads in basements, and we speak up in crowded bars.

The same could be said of stories. The best stories fit their contexts as if tailored for them. The funniest stories are told when laughter is on the horizon. The most memorable, heartwarming stories occur when hearts are ready to receive them.

So how do you gauge a situation? Start small. Don't attempt to fill the room at the first opportunity. Rather, tell a small tale, a relatable anecdote, to see how it bounces off the furniture. Then try it again.

Timing

The. Thing.

About timing. Is.

It's so noticeable and variable and personal.

Each storyteller has his or her own sense of timing that's been developed over time. In terms of learning timing, there’s likely no better medium than stand-up comedy. Great stand-ups are very similar to great writers. (And they often are great writers.) Comedians carve their acts over time. For every joke, they try different words, they test different deliveries, and they adjust their timing a thousand ways. They remember which combinations bring the biggest laughs. So by the time you hear the joke in a comedy special, it’s a perfectly polished composition.

Another way to think about timing is shower talk. Those conversations you’ve had with yourself, when you’re working out a great comeback, or you’re feeling the shapes of words in your mouth before a big interview. There’s a pace that sounds right, and you know it when you hear it. A snappy comeback too early can sound desperate; too late, it can sound weak. There’s a sweet spot to that perfect response.

Think about it this way: Tense spots in stories can be breathless and hectic, but they can also be silent. The timing and pacing depend on what the storyteller chooses, and what s/he thinks works best for the story.

Good timing requires forward thinking, and it requires some familiarity with the story or topic being discussed. It also requires a sense of the audience. Every person has a difference sense of timing and rhythm. As a storyteller, you can adjust your own timing to bring better responses from your audience.

Detail

I bring detail up last, but it's my favorite element. (Yeah, I said it. I don't care if the other elements heard me. It’s true.)

This is where my favorite storytellers shine. The details. The colorful sprinklings of color, shape, sound, and form. The black cat with the white spot shaped like a violin. The lone cricket, calling out to no one. The drops of dew resting on an orchid's petals.

When listening to any story, a person's imagination is hard at work reconstructing the scene. If the story was the script, the details would be the stage directions and props. They provide grounding, and they give the audience’s imagination a nudge in the right direction.

It's likely you've heard of Chekhov's Gun, the literary principle that argues all details in a work of fiction should be necessary to the advancement of the plot. (More specifically, if the writer places a gun in the first act, then that gun must go off later in a later act.) I think it's an extreme tenet to live by, but it's a good starting point when telling a story. The key to any good story is the storyteller's understanding of the principal parts of the plot. The skeleton, the framework, the underlying structure. Let's take, for example, the Three Little Pigs:

Three pigs build separate houses.

They build the houses with varying degrees of care.

The worst house is made of straw, the middle house is made of sticks, and the best is made of bricks.

A wolf comes to eat the pigs.

The wolf destroys the straw and stick houses, but the pigs are safe in the brick house.

The wolf tries to climb down the chimney of the brick house, and he dies.

The plot itself is rather plain when stripped to its bones, but most plots are. What makes it memorable is the telling. What are the pigs like? Where are the houses? Is the wolf bumbling, or evil and calculating? Is he drooling at the thought of pork for dinner? By how narrow a margin do the pigs escape the wolf?

The details that a storyteller chooses, and the way s/he unveils them and focuses attention on them, are what makes stories unique. You remember details. They're the breadcrumbs left along the journey. They're the pieces you remember viscerally and emotionally. They make a story come to life.

TL;DR – The Whole Story

Every great storyteller pays attention to audience, situation, timing, and detail. The success of any story is based on how a storyteller navigates all four elements.

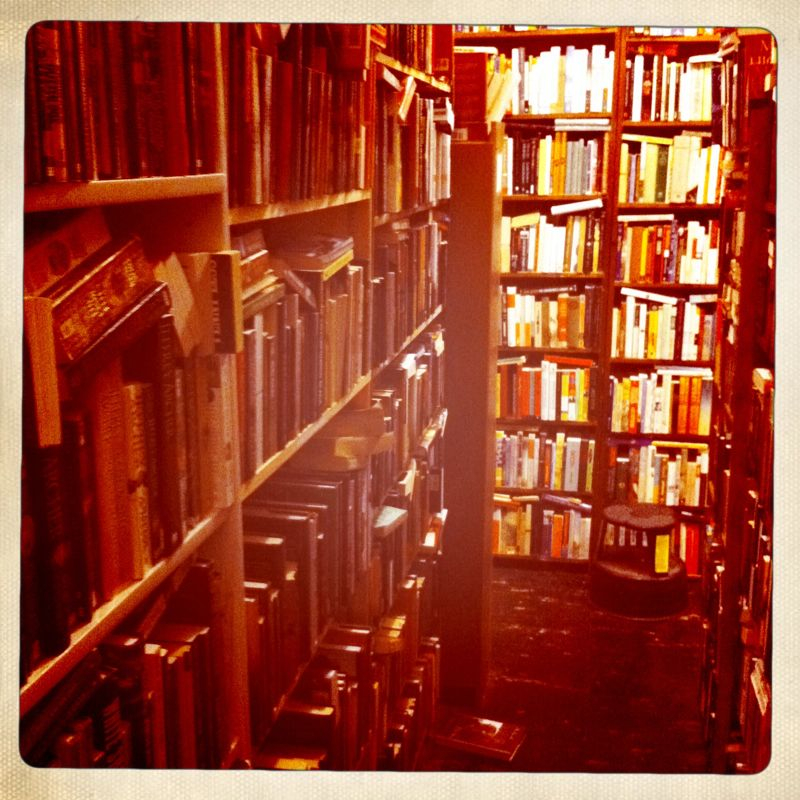

At the risk of sounding obvious, the greatest way to gain exposure to storytelling technique is by reading. Fiction authors, in particular, handle stories similarly to sculpture. They make somethings out of nothings. And because they aren’t burdened by historical truth, they are free to shape their storytelling to convey story. (That's not to say that nonfiction authors can't tell stories. I'm simply noting that as a whole, fiction offers a broader scope of storytelling technique.) For a master class, you can try a short story collection, which can throw you into world after world after world in a relatively short period of time. (You can have your own Rocky-training montage. You tiger-eyed storyteller, you.)

Go! Listen, watch, read. Live your life and pay attention. Dive deep, immerse yourself, and remember the experience. Then tell someone all about it.

* I think this relates to an article from Fast Company. In short, in seminars about making comics, Scott McCloud gives attendees five minutes to draw a random story. “What matters is clarity,” says [McCloud]. “And clarity depends on the choices you make. You must make five key choices when showing and telling any story: choice of moment, choice of frame, choice of image, choice of word, and choice of flow. That’s it.” McCloud is comic-centric in his instruction, but I think the thought is sound in multiple contexts.